The world waits for the resurrection of the CasaNegra DVD company, and the freedom from confinement of its two shelved Mexican horror releases--El mundo de los vampiros (The World of the Vampires) and La cabeza viviente (The Living Head). The former film is one of the wildest and most fascinating excursions in the vampire genre--eagerly welcome to DVD--but I consider the latter film the nadir of Salazar's eight horror films, though it has its entertainment and DVD value to be sure. Here's a brief overview of the film and its background:

Taking a week break after shooting El baron del terror (The Brainiac) at Churubusco Studios, the efficient Abel Salazar and his production company ABSA were back at the studio on March 1st, 1961, to make another horror film. Having dealt with the vampire (the Count Lavud films, and El mundo de los vampiros/The World of the Vampires), a Jekyll & Hyde (El hombre y al monstruo/The Man and the Monster), a sinister warlord (El baron del terror/The Brainiac), Salazar must have felt it was about time to give the mummy genre a chance and the same screenwriting team that gave him El baron del terror—Frederico Curiel and Adolfo Lopez Portillo—provided a script. Chano Urueta was again at the directorial helm and in familiar pre-colonial Mexican territory, having mined this terrain way back in 1933 with Profanacion, and in 1939 with El signo de la muerte and La noche de los Mayas.

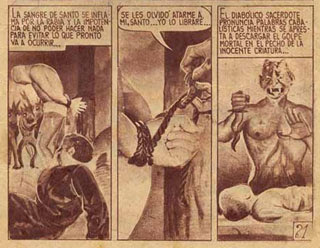

Borrowing for its credits the main theme from El baron del terror, the film opens with stock shots of the Aztec world (possibly taken from one of Urueta’s earlier films) and then a sacrifice of a traitorous Aztec warrior whose heart is cut out of his body by Xiho, the high priest. (The heart, dripping with blood, is a novel sight for the time of the film's exhibition, though the gore intensity is muted by the film’s black and white palette.) Thereafter we learn that the traitor had caused the death and beheading of great warrior Acatl. Xiho (Guillermo Cramer) is entombed with the head, as is the high priestess Xochiquetzal (Ana Luisa Peluff0). Over four centuries later, in 1963, an archaeological expedition led by Professor Herman Meuller (German Robles) uncovers the sealed tomb. The change in air pressure causes Xochiquetzal's mummy to vaporize, leaving for the taking Acatl's head, the perfectly preserved body of Xiho (which doesn't vaporize), and a large ring that, unknown to the expedition, reveals in its jewel the person destined to die in connection with Acatl and the tomb's desecration. Anyone familiar with Mummy films can guess the rest of the plot.

La cabeza viviente was first exhibited in Mexico in 1963, which required the changing of the time-line from 1961, the year of the film's production. (You can spot the change: A different font is used for displaying the year 1963 in the time-line dissolves that proceed from Aztec times.) The film’s working title, El ojo de la muerte (The Eye of Death), refers to the ancient Aztec ring already mentioned.

Urueta’s direction is rather pedestrian for this outing, possibly reflecting the speedy shoot and the bareness of certain areas of the script. The climax is particularly poor, with Professor Meuller, as the father of the main female character (who is, of course, spiritually connected to the Aztec high priestess, Xochiquetzal) trying to rationalize with a bewitched character (Robert, the male romantic lead played by Mauricio Garces) into not killing his daughter, rather than stepping in to physically stop him. It's an absurd scene, making the father appear cringing and cowardly, and German Robles overacts throughout, as if never receiving any direction from Urueta during this crucial climax.

Furthermore, the K. Gordon Murray dub, The Living Head, which is most familiar to Americans, is filled with classic bad-film lines and a sonorous, portentous reading by dubber Paul Frees of Robles’ lines that gives the film extra humor value where none was originally intended.

La cabeza viviente is the most predictable of Salazar’s movies, nowhere near as outré as his other horrors, and revisiting territory recently covered in Mexican and world horror cinema. It offers almost nothing in the way of innovation.

One might have supposed that, with this film, it was time for Salazar to call it quits and end his mining of horror themes, but there was one more film destined to emerge from his ABSA production company, a masterpiece that ended the horror reign of Salazar with a bang--La maldicion de la Llorona (The Curse of the Crying Woman).